|

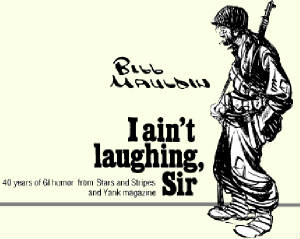

Bill Mauldin With Willie And Joe

Cartoonist Bill Mauldin, friend of GIs as creator of 'Willie and Joe,' dies at 81

By Patrick

J. Dickson

Stars and Stripes

Published: January 23, 2003

As they trudged back home from the trenches of World War II, U.S. soldiers would tell stories of how they knew they couldn’t

lose because they had a secret weapon on their side.

It wasn’t a gun or a bomb, but a fellow soldier named Bill Mauldin, who took pen to paper and depicted the horrors

of war, often with sharp-edged humor.

"I'm convinced that the infantry is the

group in the army which gives more and gets less than anybody else."

Mauldin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist best known for his drawings in Stars and Stripes, died Wednesday. He was 81.

One of the 20th century’s pre-eminent editorial cartoonists, Mauldin died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease,

including pneumonia, at a Newport Beach, Calif., nursing home, said Andy Mauldin, one of the cartoonist’s seven sons.

Mauldin, who was an Army rifleman, drew a pair of tired and downtrodden soldiers named Willie and Joe, whose wry observations

of life on Europe’s front lines were loved by soldiers and loathed by many in command, including Gen. George S. Patton.

Andy Rooney, a commentator for CBS’ “60 Minutes,” worked for Stars and Stripes with Mauldin during World

War II.

"I don't make the infantryman look noble, because he couldn't look noble even if he tried. Still there is a certain

nobility and dignity in combat soldiers and medical aid men with dirt in their ears. They are rough and their language gets

coarse because they live a life stripped of convention and niceties. Their nobility and dignity come from the way they live

unselfishly and risk their lives to help each other."

“There was one cartoon that just infuriated Patton,” Rooney said in a recent phone interview. “There

was a Patton-type general with one of his aides, and he was looking over this beautiful vista, and he says to the aide, ‘Is

there one of these for the enlisted men?’

“[Mauldin] was quite shy. He didn’t come on very strong. He sat in the corner watching the world go by,”

Rooney said.

|

|

| Bill Mauldin and Andy Rooney in 1992 |

William Henry Mauldin was born Oct. 29, 1921, in Mountain Park, N.M., the son of a hard-drinking jack-of-all-trades who

moved the family around the Southwest and northern Mexico during the Depression in search of work.

"My

outlook on warfare is best illustrated by a cartoon I did of a soldier in an Italian foxhole reading about the Normandy

invasion and observing to his buddy that: "The hell this ain't the most important hole in the world. I'm in it."

At 13, Mauldin saw an ad for a correspondence course in cartooning in Popular Mechanics magazine that claimed one could

earn as much as $100,000 a year. Mauldin borrowed the $20 tuition from his grandmother and enrolled. A teacher in high school

helped him further nurture his talent, and he attended the Academy of Fine Art in Chicago.

Mauldin enlisted in the Army in 1940 and, assigned as a rifleman to the 180th Infantry, started drawing cartoons depicting

training camp for the Division News, the newspaper for the 45th Division.

Once Mauldin’s 45th Division shipped overseas, Stars and Stripes began publishing his drawings.

"I was a born troublemaker and might as

well earn a living at it."

Mauldin called himself “as independent as a hog on ice,” and his nonconformist approach occasionally brought

him trouble from the top.

Meeting Patton

A meeting between Patton and Mauldin was arranged after Patton threatened to stop distribution of Stars and Stripes in

3rd Army areas because of cartoons and photographs which depicted soldiers in “unsoldierly” appearance.

Mauldin recalled the meeting in his book, “The Brass Ring,” published in 1972: “There he sat, big as

life even at that distance. … A mass of ribbons started around desktop level and spread upward in a flood over his chest

to the top of his shoulder, as if preparing to march down his back, too.

“‘Now then, sergeant, about those pictures you draw, where did you ever see soldiers like that? You know damn

well you’re not drawing an accurate representation of the American soldier. You make them look like bums. No respect

for the Army, their officers or themselves.’”

Patton grilled Mauldin about his cartoons, finally telling Mauldin that they “understand each other now.”

"I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark

Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn't like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques

he used to get his men out of their foxholes."

Mauldin wrote: “Years later, I read of Patton’s reaction when [Gen.

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s aide, Navy Capt. Harry] Butcher read my account of the meeting to him over the phone.

When he quoted me as saying I hadn’t changed the general’s mind, there was a chuckle. When he came to the part

about his not changing my mind, either, there was a high-pitched explosion and more talk about throwing me in jail if I ever

showed up again in 3rd Army.”

Well known by now is the story of Gen. George Patton threatening to have The Stars and Stripes banned

from the Third Army as long as Mauldin's unkempt heroes appeared in it. Patton and Mauldin were told by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower's

headquarters to discuss the matter. Said Mauldin after the conference: "I came out with all my hide on."

After the war

After he left the military, Mauldin did freelance work. He joined the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1958, and moved to the

Chicago Sun-Times in 1962.

It was at the Sun-Times that he drew one of his most poignant and famous cartoons when President Kennedy was assassinated.

The drawing showed a grieving Abraham Lincoln, his hands covering his face, at the Lincoln Memorial.

But for World War II veterans, Mauldin will be best remembered for uplifting their spirits during the darkest days of the

war.

"The

combat man isn't the same clean-cut lad because you don't fight a kraut by Marquess of Queensberry rules. You shoot him in the back, you blow him apart with mines, you kill or maim him the quickest

and most effective way you can with the least danger to yourself. He does the same to you. He tricks you and cheats you, and

if you don't beat him at his own game you don't live to appreciate your own nobleness. But you don't become a killer. No normal

man who has smelled and associated with death ever wants to see any more of it. In fact, the only men who are even going to

want to bloody noses in a fist fight after this war will be those who want people to think they were tough combat men, when

they weren't. The surest way to become a pacifist is to join the infantry."

Many of Mauldin’s admirers had showered him with letters of thanks in recent years as his health slowly declined.

Mauldin is survived by former wives Jean Mauldin and Christine Lund and all of his sons. Burial is planned in Arlington

National Cemetery.

Funeral Services

His life was remembered by Chaplain (Major) Douglas Fenton and about 50 mourners, mostly family, that

gathered in a cold drizzle to pay their respects. The chaplain listed war heroes

and leaders buried at Arlington, then spoke of “the man we honor today, loved by the ‘greatest generation,’

a man who led hearts and warmed smiles” with his distinct talents. Fenton mentioned one of the thousands of letters

Mauldin received while in the nursing home, relaying that the soldier said Mauldin’s “humor kept them moving forward,

even in the face of adversity.”

And with the Pentagon behind them in the distance, seven soldiers from the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment,

The Old Guard, fired three volleys into the cold air for Mauldin, a Purple Heart recipient. After Taps was played, Sergeant

Major of the Army Jack Tilley took the flag from the honor guard and presented it to Sam Mauldin, the 16-year-old son of the

Pulitzer Prize-winning artist.

One of Mauldin’s

other sons, David, spoke after the ceremony. Before taking questions, he insisted that those who wrote to his father in the

last months of his life be thanked. “The family is so grateful to the soldiers and veterans who wrote to Dad at the

nursing home to express their thoughts and feelings. It really made a difference to Dad.” Though Alzheimer’s disease

had begun to rob Mauldin of his faculties, he still understood the significance of the gestures. “It’s hard not

to understand, when boxes of letters and mementos come into your life, that you’re still important to people,”

David said.

Newspaper columnist Bob Greene wrote in August that the cartoonist was in failing health, and provided

an address where admirers could send their wishes. Asked how many letters his father had received, David paused.

“A couple of months ago, it went past 10,000,” he said.

The younger Mauldin noted, as did many at the brief ceremony, that the cold and drizzle was the perfect

setting for his father’s funeral. “It would make sense for him to die in the middle of winter, in terrible weather

with lots of mud,” he said. It was so dismal one had to wonder if Willie and Joe, his bleary-eyed protagonists in many

a cartoon, were not there in spirit.

David Mauldin recalled a cartoon in which his father captured the camaraderie of soldiers at the front.

Sitting down in the reeds, their feet lost in the muck, Willie thanks his buddy with the best gift

he could give, given the circumstances. “Joe, yestiddy ya saved my life an’ I swore I’d pay ya back. Here’s

my last pair of dry socks,” reads the caption.

“One person sent me a pair of socks,” David said. “A guy named Bill Ellis sent the

socks after [Dad’s] death. That moved me to tears.”

And he started to cry.

|

|

| Bill Mauldin tombstone at Arlington Nat'l Cemetery |

More Willie And Joe

|